On Whitesplaining, Overcoming Poverty, and Being an Ally | Diana Skelton

By Diana Skelton

My cell phone is flashing.

Martine Le Corre is texting me: “I’m stuck with frustration.”

She and I just separated after taking part in a study day at Paris 8 University. We and Magdalena Brand made a joint presentation there about the violence of extreme poverty. Many people told us they appreciated it but Martine’s frustration is with one participant who was upset with us. Her anger was about “intersectionality”, an approach to social justice work that emphasizes how oppression and discrimination are influenced by many aspects of identity: gender, race, ethnicity, religion, class, nationality, sexuality, disability, illness…

Martine, Magdalena, and I spoke about the intersection between gender and poverty. One of our points was that feminist movements remain driven mainly by the concerns of middle-class women, with almost no attention given to the issue cited as the most vital by women living in poverty in western Europe: the patriarchy of social services. But the woman criticizing us from the audience was frustrated that we did not differentiate the experience of black women. She said, “Whenever race isn’t named, black women are lost.” She’s right but Martine’s frustration is that women in poverty, of any skin color, also get lost too easily.

Martine grew up in extreme poverty. At age 18, she says, “I had ended up believing that I wasn’t worth much, that I was a ‘misfit,’ ‘antisocial,’ just dirt poor and nothing but poor. […] I had never felt allowed to use words [like intelligence and knowledge] about myself.”(1) But Martine has a keen intelligence, and since then, she has spent forty years investing it on behalf of all those she calls “my people.” Her people may be anywhere in the world, but they have in common growing up with the feeling that they are useless, nothing expected of them. The talk we gave together was about an action-research project that Martine co-directed showing that poverty is a form of violence. In our talk, Martine spoke about her neighbor who is insulted at every turn. Told that she is unworthy of raising her own children, the neighbor was made to listen silently to a roomful of social service staff listing her every fault and then accused of violence and led away by security officers when finally she slammed a cup on the table in frustration. “Treating her that way is institutional violence that destroys lives,” Martine said, “but what is done to us is never considered violence. Calling it violence would disturb society. So the violence done to us stays invisible. Enough! Extreme poverty is violence, society can’t accept it any longer.”

So often people who grow up in poverty share Martine’s experience of not considering herself worthy or smart. In the face of prejudice and judgement, they are told to keep quiet and listen. Their attempts to break the silence can be considered violent. “Whitesplaining” happens when white people hijack conversations about racism by trying to speak in the place of people of color.(2) Men who speak in a patronizing way to women are “mansplaining.” So what word could we invent to describe what happens when people in poverty are patronized in the same way? “Top-downsplaining”?

What all social justice movements need is for each person to be heard speaking about her or his own experience, and for people without personal experience of being marginalized to become allies. It’s in the word “ally” that we can find a powerful connection with the same social justice movements that don’t yet have a word for the silencing of people in poverty. Ten years ago, in English, the word “ally” was hardly ever used outside of the context of World War II history. But in 2007, it was added to the Urban Dictionary of modern slang to mean “a person who is not gay but supports the rights of lesbian, gay, transsexual and bisexual people.” Today, that definition has been broadened to other marginalized groups and also sharpened to include making it clear that a good ally has a very specific role.

Franchesca Ramsey hosts MTV’s “Decoded”, a vlog about overcoming racism and other prejudice. She defines the role of an ally as:

“someone who wants to fight for the equality of a marginalized group that they’re not a part of. … An ally’s job is to support. You want to make sure that you use your privilege and your voice to educate others but make sure to do it in such a way that does not speak over the community members that you’re trying to support or take credit for things that they are already saying. Speak up but not over.”(3)

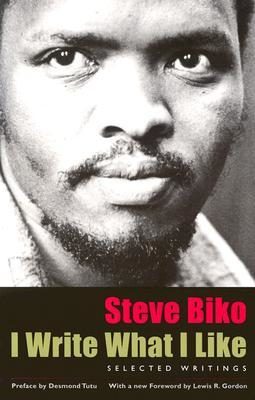

In 1970, Steve Biko, a black anti-Apartheid activist who was later tortured and murdered by the South African police, described the role he saw for white liberals:

“The role of the white liberal in the black man’s history in South Africa is a curious one. Very few black organisations were not under white direction. True to their image, the white liberals always knew what was good for the blacks and told them so. [] That bunch of do-gooders goes under all sorts of names liberals, leftists etc. These are the people who argue that they are not responsible for white racism. [] All true liberals should realise that the place for their fight for justice is within their white society. [] The liberal must apply himself with absolute dedication to the idea of educating his white brothers that the history of the country may have to be rewritten [so] that we may live in a country where colour will not serve to put a man in a box.’”(4)

Both Franchesca Ramsey’s and Steve Biko’s words call to mind the vision of Joseph Wresinski, founder of ATD, for what he called:

“a new alliance between established members of society and people in poverty. [] To be faithful to this alliance, we will follow through completely our challenge to any of society’s projects that exclude the weakest. We will impose, in every field, the participation of the most disadvantaged, [] denouncing everything that puts a person in a situation of inferiority and leads to his rejection by others, [and calling for] a project for the whole of society in the name of defending the most underprivileged and the respect of their rights.”(5)

Allies of people in poverty have an important role to play in challenging their own colleagues, neighbors or relatives but it is also crucial that they make room for others to hear the voices of people in poverty directly, without silencing or interpreting people’s words.

After our day at Paris 8 University, Martine said, “When she was shouting at us, I kept thinking of my people. It’s that kind of attitude that can divide us, helping politicians who want to pit us against each other, breaking solidarity.” An ally of ATD Fourth World in New York, Rosa Cho, spoke to us about a time when she felt that a group of protestors was pitting different causes against one another. But when she gained some distance from her first emotions, she says she realized, “my own subjectivity is ill-equipped to understand and feel the depth of their particular pains, sense of desperation, hopelessness, and not-understoodness.”

All of us need solidarity so badly. There are many forms of prejudice and of systematic oppression that damage the whole of society by short-circuiting people’s potential and ignoring the contributions they make. In order to strive toward solidarity, how can each of us explore more fully what it means for us to become an ally to someone whose personal experience of oppression, prejudice, and “not-understoodness” is different from our own?

1 As quoted in chapter 2 of Artisans of Peace Overcoming Poverty.

2 “White People Whitesplain Whitesplaining”, an MTV Decoded video by Franchesca Ramsey.

3 “5 Tips for Being an Ally“, an MTV Decoded video by Franchesca Ramsey

4 Biko, Steve, I Write What I Like: Selected Writings, Black Souls in White Skins, 2002.

5 Speech on 17 November 1977 in Paris, France.