Hernán Mamani: Volunteer Corps Member

Born in Argentina, Hernán Mamani studied sociology in Brazil, where he spent much of his life. From an early age, he was involved in social justice and democracy movements in both countries. Today, Hernán is a new Volunteer Corps member working at the Joseph Wresinki Archives and Research Centre (JWC) in Baillet-en-France. He explains why he became a Volunteer Corps member and what he’s learned about poverty—and about himself.

“At first, I was reluctant to get involved”

ATD Fourth World was presented to me as a way to fight extreme poverty. At first, I was reluctant to get involved. I knew about extreme poverty, but I had a hard time seeing it as a cause. I wasn’t sure how relevant it was to me.

But my thinking on this changed when I began to question some of my former beliefs. Back then, the issue of poverty for me was very much associated with religion. And I often disagreed with religion. I wasn’t against the ethics of Christianity, especially values such as simplicity or treating everyone equally. In fact, I believe in these values and try to live by them. But I didn’t agree with other aspects of the Church and was I more interested in changing the world than changing people’s souls.

Social activism in Latin America

Wanting to change the world led me to join the struggle for democracy in my country, Argentina. I fought for decent work and free university education, and to get rid of compulsory military service. Then in Brazil, I learned so much and developed new interests. Social justice movements in Latin America caught my attention. I became more interested in the social sciences and decided to focus my studies on this field.

So I became a poor student, active in militant student movements. I was close to the Brazilian Workers’ Party. During this time, I lived through Brazil’s return to democracy and then Argentina’s, a country very similar to Brazil.

- Both countries’ constitutions stated that social rights, and human rights in general, were very important. But this was only on paper.

With these new constitutions came neoliberal governments that ended up completely delegitimising the very concept of human rights.

As a result, in the 1990s, many of the movements that had contributed to the triumph of democracy fell into crisis or simply dissolved. It was in this environment that I started doing informal jobs, first as a student and then as an unemployed young graduate. However, my work experience prompted me to go back to university in order to study these issues further.

“We were in the same camp”

A lot of policy is built on widespread but inappropriate theories. As a result, implementation is totally ineffective. I was discovering that there is a huge gap between scientific, or technical, knowledge and the kind of knowledge that people in extreme poverty have. However, I never thought of poverty itself as a research topic.

This changed when I came across ATD Fourth World-France’s website where I read about the organisation’s activities and goals:

- Grassroots work to unify people in efforts to attain their rights.

- Collaborating with people in poverty to advocate for change in laws and how they are implemented.

- Changing perceptions of people in poverty and urging public support for efforts to overcome poverty.

My perspective on human rights changed after I read a short book by ATD Fourth World’s founder, Joseph Wresinski. Wresinski insists that all human rights are connected because all human beings are connected. In the book, he criticizes the way that rights are recognised on paper yet ignored in practice. Wresinski also says that it doesn’t make sense to talk about a hierarchy of rights. In fact, ranking some rights as more important than others leads to both the existence and perpetuation of extreme poverty. Reading this, I saw that we shared a lot of the same ideas. In fact, we were in the same camp and had common goals.

A culture of community

Then something significant, although quite different, happened. My family and I went to live at the ATD Fourth World International Centre in Méry-sur-Oise, France. When we arrived, people we didn’t know at all welcomed us so warmly, in a way that I had never experienced.

Over time, I saw that this welcoming atmosphere was both lasting and genuine. I discovered a culture of community there, developed through living together and supporting each person as an individual. This helped me see the Volunteer Corps as a way of life that I had never encountered before.

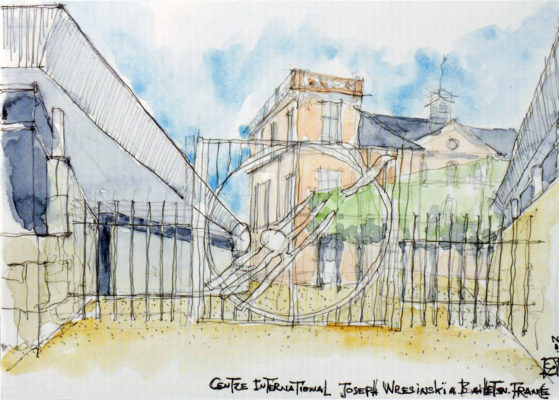

At the Joseph Wresinski Centre, my team was equally welcoming and supportive. After reading Here Where We Live: Wresinski, Poverty, and Human Rights in Latin America and the Caribbean, I began working in the archives and summarizing books in Spanish.

Through this work I discovered something very important for me. I began to see that there is a key ethical problem in the power imbalance that exists in relationships. The ATD movement believes in equality and respect among all people. This explains the role of the Volunteer Corps, whose members try to live out and encourage respect and equality in all their interactions.

Reading Here Where We Live and other writings reminded me of the work I had done with my research group in Brazil. However, these works helped me see better answers to the urgent crises we currently face in policy, epistemology, and democracy.

Part of the history of emancipation movements

I find ATD Fourth World to be an organisation with ideas that are original, smart, and carefully thought-out. In fact, I see ATD as part of a great history of movements fighting for emancipation. Of course, it is very much shaped by French traditions, but also by worldwide movements for workers’ rights and freedom from oppression.

However, in my opinion, what makes ATD Fourth World unique is the many ways that its founder, Joseph Wresinski, shaped the organisation based on his work at Noisy-le-Grand in the movement’s early years.

ATD Fourth World’s original way of working helps avoid some of the dead ends where other movements lost their way. Here I am thinking of socialism, labour movements, and institutionalised social protection systems, particularly in the Marxist-Leninist labour movements.

Like these movements, Wresinski recognised that people can change the world and progress has been made. The labour movement has always agreed.

- But Wresinski found a way to avoid creating an elite, something that often led the labour movement to abandon the rest of the population. ATD avoids this tendency by focusing on people in the deepest poverty, by constantly seeking them out. As they say, behind one person in poverty, there is always another in greater poverty.

ATD Fourth World is not a movement that seeks power or violent change, quite the opposite. It is a movement that promotes a change in culture.

A unique social experiment

ATD Fourth World activists are people living in poverty every day. This is very significant. Volunteer Corps members manage the organisation and keep everyone on the same page. But Volunteer Corps members are also responsible for developing and maintaining a community. I find this to be a unique form of social experiment.

One of the most important results is that ATD’s way of living and working avoids several other potential pitfalls. On the one hand, we avoid becoming a bureaucracy, which often leads an organisation to lose sight of its original goals. On the other hand, there is no “elite” that could lead to militant leaders dominating those who have less power or strength.