The Causes of Epistemic Injustice

This article is part of our series from ATD Fourth World’s Social Philosophy Project. It is adapted from talks by Bruno Tardieu ATD Fourth World Volunteer Corps member and Marie-Joe Lebreton, an ATD Fourth World activist with lived experience of poverty, at a regional seminar in France. This article highlights some of the causes of epistemic injustice and was published in Pour une nouvelle philosophie sociale.

Bruno Tardieu

There are many causes of epistemic injustice, but I want to highlight three: epistemic vices, stereotypes or prejudices, and the hierarchy of knowledge.

According to philosopher José Medina, those who hold dominant positions in social hierarchies “are used to being considered competent, […] being listened to and [being] recognized.” This means that they are seldom questioned cut off, or told that they are wrong. As a result, they have great self-confidence in their relationship with knowledge. This means that those who belong to a dominant group can develop intellectual attitudes that impede their ability to acquire knowledge, as they have no impetus to take into consideration the experiences and knowledge of others.

Epistemic vices

Such attitudes are called “epistemic vices”, and, though they are not voluntary, they are condemnable. Some of Medina’s examples of epistemic vices are as follows:

- “Epistemic arrogance”, where the dominant embodies an exaggerated sense of self-importance in their knowledge, believing and behaving as if they (solely) know everything.

- “Epistemic laziness”, where the dominant experiences an absence of curiosity about the lives of people who are not like them.

- “Closed-mindedness”, where the dominant is unable to acknowledge their own limitations, and believes knowledge other than their own must be false.

Negative stereotypes

A second cause of epistemic injustice are negative stereotypes, which carry symbolic violence. Stereotypes are particularly numerous in the context of extreme poverty, where people living in poverty are frequently misrepresented as parasites who take advantage of the system. These stereotypes lead to the “naturalization” of poverty, wherein poverty is perceived seen as a personal failing, as opposed to a situation created by the social and political choices of a wider society.

Unequal value

A third cause of epistemic injustice is the unequal value given to different types of knowledge. Knowledge exists in a hierarchy in contemporary societies, and scientific knowledge is most often at the top of this hierarchy. Other types of knowledge, such as knowledge derived from experience, are considered inferior or of lesser importance.

After describing these three causes of epistemic injustice, we look for remedies.

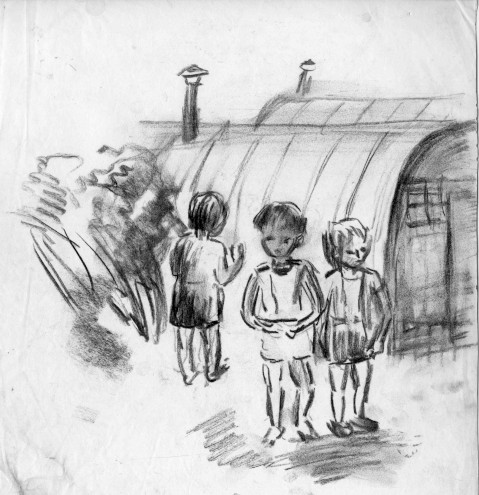

Marie-Joe Lebreton

A remedy to the epistemic injustices described above is mutual respect and a willingness to listen. Together, they create space for people who have difficult lives to make themselves heard and understood. Without respect and a desire to listen, people are reduced to silence and shame.

At the same time, shame has the power to make us react to and reflect on our experiences and relationships with others, which opens up a path towards liberation. Shame can be channeled into positive outlets, but only on the condition that we do not remain locked in on ourselves.

School

For me, school was painful in the beginning, and I suffered. I tried hard at school to respond to this situation, and I got through it.

The friends I made at school made me want to be like them, and I opened up thanks to neighbours my age. They opened my eyes. When I went home after school, instead of staying with my foster family, I went to friends’ houses, where they were friendly towards me and I could talk to them about what I was going through. There was trust, and my words had weight. We did a lot together, and became as close as sisters. This was a turning point, and helped me take responsibility for my life.

ATD Fourth World activist

For the past few years I have been an ATD Fourth World activist, which allows me to reflect with others who understand me, even if we have different life experiences. Being listened to and respected (by my friends at school, and now the co-researchers of the Social Philosophy Project), being heard and understood, and being recognized and accepted restores confidence. It allows you to come out of isolation, to react to shame, and to be proud of yourself! Since participating in the Social Philosophy Project research, where different forms of knowledge intersected, I have read more and dared to speak more. Now I want to continue learning and sharing with other people what I know.