Tribute to the Victims of Institutional Maltreatment, Today and Yesterday

By Mariana Guerra and Eduardo Simas from Brazil, Mogène Alionat and Laura Nerline Laguerre from Haiti, and Carine Parent from France.

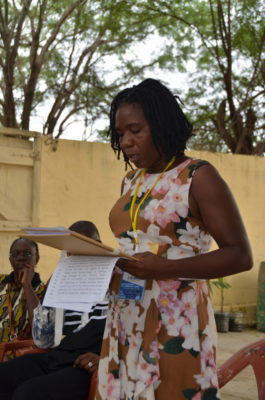

This article is based on a speech delivered at the House of Slaves museum on the Island of Gorée, Senegal, on 18 October 2024 as part of the events related to the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. Read about the historic link between House of Slaves museum and ATD Fourth World.

Senegal, October 2024

The Atlantic slave trade claimed more than fifteen million victims. Uprooted from their land, their families, and their culture, these people were sent to Haiti, Brazil, and other countries of the Americas. It is estimated that over two million of them lost their lives during the crossing and were thrown into the ocean. For those who survived, it was hell. Moreover, the lands they were sent to were already inhabited by Indigenous peoples who were being brutally exterminated.

Deprived of their identity, they were considered merchandise rather than human beings. They were exploited and subjected to numerous forms of violence. They were denied the right to their cultural identity, their spirituality, and even their own name. The institutions established at the time — churches, governments, and economic powers alike — were complicit in this immense atrocity and supported it extensively.

Today we still bear the scars of that period, which mark our bodies and our entire existence. Scars also result from many practices which, even today, subject a large part of the population on both sides of the Atlantic to unbearable situations of deep poverty and exclusion.

Surviving the inhumane system of slavery required resistance, strength, and intelligence, which these men and women learned to develop. Whether by organizing themselves and becoming Maroons, rebelling against their masters, or creating solidarity networks on the plantations — and always looking for other strategies — they fought for their freedom. In Haiti, these acts of resistance by enslaved people culminated in an uprising. On the night of 13 to 14 August 1791, a man named Boukman who had escaped from slavery, organised a political and religious ceremony at Bois-Caïman with a large number of people who had been taken in slavery from various African tribes. The Mambo priestess, Cécile Fatiman, sacrificed a black pig, whose blood the attendants drank to become invulnerable. Boukman then ordered a general uprising. Vodou was a catalyst in the revolt of enslaved people in Haiti. The founding of Haiti was the culmination of the anti-slavery insurrection led by these Maroons in 1791. This led to the country’s independence in 1804, putting an end to more than three centuries of colonisation.

We are all indebted to this revolt, which marked a turning point in the history of humanity and had a considerable impact in affirming the universality of human rights and the dignity of each person.

Haiti is the land where enslaved people offered freedom to the world. It has also helped other countries to obtain their own freedom. Haiti is the symbol of freedom. But this independence is not without consequences for our existence as a people. The international community refused to accept Haiti’s independence and ceased all trade with the country. Further weakening the fledgling nation, the former coloniser demanded economic reparations. The young country was forced to pay off this unjust debt, which considerably hampered its development and affected the future of every Haitian, plunging the people into deep poverty that continues to this day.

More than two hundred years after slavery ended, we are no longer held in chains, but the scars remain. They are expressed in social injustice, racism, oppression, and systemic domination. Indeed, a certain world order, shaken by the revolts of enslaved people, persists in its pursuit of domination rather than peace. The imperialist countries continue to thrive, receiving in huge numbers people who have been overburdened by their policies. Uprooted, the newcomers serve the economies of these powers, weakening the development of their own countries. It seems clear that Haiti is paying for its boldness in daring to give others a taste of freedom.

Despite everything, Haitians continue to believe in a better future. Economic and moral reparations, although necessary and urgent, will never erase the pages of this history. But at least we can rewrite it in a more just and dignified way.

Today, we are here as part of ATD Fourth World to pay tribute to people who have suffered from institutional maltreatment today and in the past; but we are also here to recognize the strength of resistance of those who fought for their freedom, not only for themselves but also for all the peoples of the earth. Haiti was a great example that showed the world the strength of collective struggle for the liberation of all. But the struggle is not over, and we continue to resist. We insist on keeping alive our roots, our culture, and our ancestral spirituality, and on rebuilding the ties that bind us to this land, until one day all peoples are recognised and acknowledged for who they are.

Today, we are here as part of ATD Fourth World to pay tribute to people who have suffered from institutional maltreatment today and in the past; but we are also here to recognize the strength of resistance of those who fought for their freedom, not only for themselves but also for all the peoples of the earth. Haiti was a great example that showed the world the strength of collective struggle for the liberation of all. But the struggle is not over, and we continue to resist. We insist on keeping alive our roots, our culture, and our ancestral spirituality, and on rebuilding the ties that bind us to this land, until one day all peoples are recognised and acknowledged for who they are.