A Visit to Apartheid South Africa: Immense but Hidden Potential

This video is the seventh in a series retracing the life of Mary Rabagliati, who helped Joseph Wresinski co-found ATD Fourth World.

Play with YouTube

By clicking on the video you accept that YouTube drop its cookies on your browser.

After Mary had spent eleven years supporting families in extreme poverty in England, France, and the United States, she enrolled at the London School of Economics to prepare herself for taking on greater responsibility for ATD Fourth World. One of her fellow students was a South African woman who invited Mary to go on a six-week study trip to South Africa.

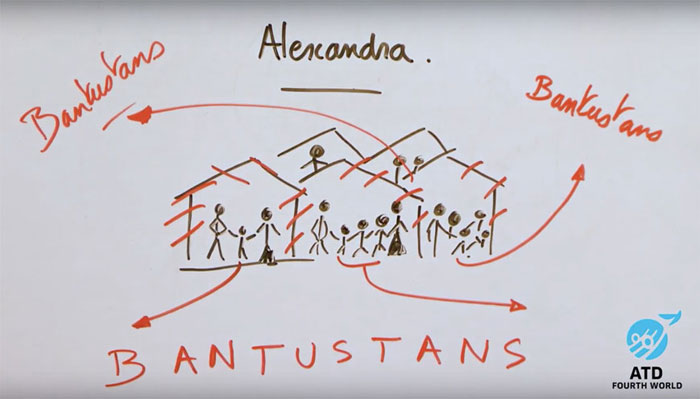

Since 1948, South Africa had been governed under a system of racial segregation and discrimination known as apartheid — a word meaning ‘separateness’ — for the benefit of the white population. Throughout the 1970s, the apartheid government in South Africa carried out the mass removal of 3.5 million non-white South Africans from their homes to ten designated Bantustans, referred to by the government as ‘homelands’. Mary’s visit to South Africa took place in the midst of this period of upheaval in May and June of 1973. Her goals were to discover and learn from the ways people were trying to resist this extreme form of exclusion.

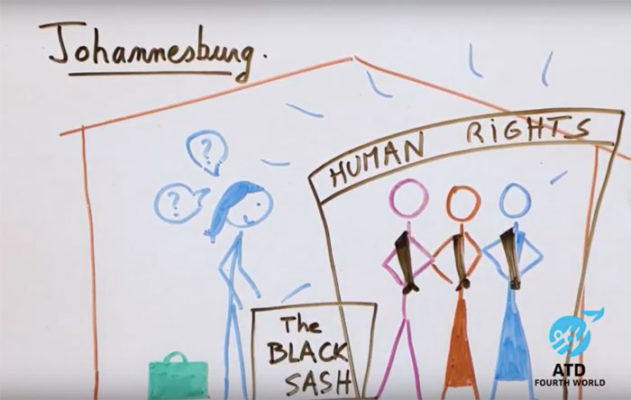

Mary’s first stop was Johannesburg, where she was hosted by Beyers and Ilse Naudé, prominent anti-apartheid activists. They arranged for her to visit Alexandra, a black township located between Johannesburg and Soweto. Black South Africans had previously lived in Alexandra as families; but under the new ‘homelands’ policy the government had demolished their homes and sent the children and grandparents away to the Bantustans. Dormitories were being constructed to house the 60,000 workers who remained. Here is Mary’s description of her visit to one of the women’s dormitories:

“It was designed to house 2,000 women, although so far only 700 have moved in. There is only one entrance, which is guarded; and electric gates are installed within the building so that any part of it can be isolated at any time. Throughout my visit, I was accompanied by a white female guard. Many of the women in the dormitory are domestic workers who used to spend nights in the homes of their white employers. But a new law forbids black people to sleep at their workplace, which is why the dormitories have been built. Women sleep four to a room. For every fourteen women, there is one toilet, one sink, and one cooking burner. No men are allowed in the building except in a single visitors’ room furnished with plastic benches and tables.”

Mary was appalled. Following that visit, she brought up the subject with most of the black South Africans that she met. They told her that black people hate the dormitories and consider them to be a violation of family life. They also pointed out that the area surrounding these dormitories was plagued with violence, including sexual assault.

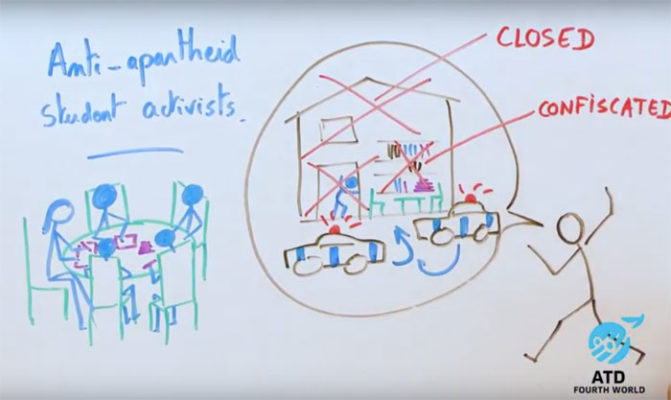

Unlike the United States where people openly protested against injustice and racism, Mary discovered that in South Africa there was no freedom of speech whatsoever. Those who tried to resist were often imprisoned without explanation. The press was tightly controlled, and there was a strong atmosphere of suspicion everywhere. Mary wrote:

“No one here trusts anyone, because anyone could be an informant ready to denounce you to the government. So you always have to be very careful indeed of what you say. This creates the most oppressive sense of isolation that I have ever felt anywhere. Usually, I’m completely frank; but during my time in this country I have to be very careful because anything I say could be used against others after I leave.”

Looking back on her visit, Mary observed that “black South Africans clearly have an immense potential; but this potential is mostly hidden because the adults must work such long hours that they have very little energy left for anything else.” Determined to gain a wider perspective, she decided to visit some of the newly independent nations of Africa to learn how people in those countries were struggling against poverty and exclusion.

This and the content of other videos in the series will be published in Joyful Revolution: Poverty, Social Justice, and the Story of Mary Rabagliati. [Publication date, October 30, 2025]