We Met under the Mango Tree

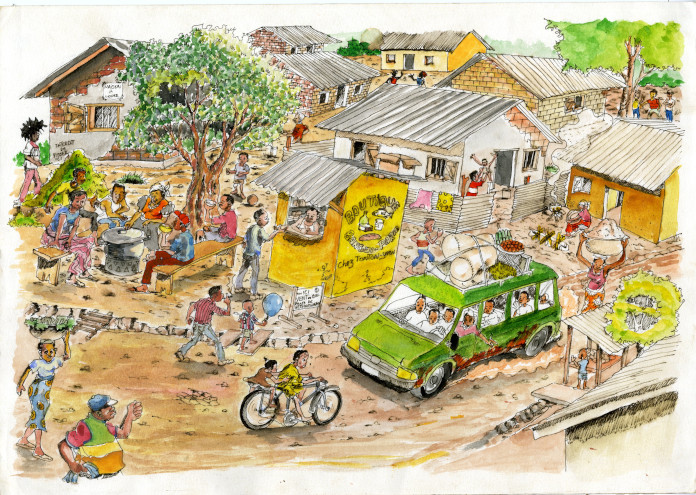

Drawing above : Aquarelle, town centre, Bangui, Central African Republic, 2011 © Yvon Gandro/Collection Brand/Centre Joseph Wresinski – AR0207001003

“It’s our ties that are radical.”

This is how Simeon Brand, film director and member of the ATD Fourth World Volunteer Corps, introduced one of his short films. Made in Central African Republic (CAR), the documentary is called À nos enfants et jeunes, bâtisseurs de paix (To our children and young people: peacemakers). In the film, people in CAR talk about how they’ve made progress together and what they’ve built in the midst of poverty and armed conflict.

One young farmer explains how, during the war, he plucked up the courage to help the most vulnerable children:

- “The ATD Fourth World movement is like a garden. You have to take care of children so that they grow. That’s why I became a youth worker for the Street Library. I didn’t want these children to lose their lives, their dignity, or their worth. It’s important for them to have their own place in the community. In fact, they’re intelligent and capable of contributing something to our country. Violence against these children, that really upsets me.”

A kind of disarmament

In one conversation, Mr Parfait, a Fourth World activist, talks with Geoffroy, a social-cultural mediator. Mr Parfait describes the Street Library, which takes place outside on a special woven mat that covers the bare ground.

- “This mat that we’ve woven here always gathers the children together. We put on plays, sing, and do other fun things. And we make sure that all the children fit in. Even the blind child – when he’s surrounded by us, it’s great for everyone. The Street Libraries don’t destroy anything. That’s why I say they’re a kind of disarmament.”

Geoffroy wanted to know more, so Mr Parfait added:

- “This right of children to be together is really precious. Here, children gather together under their parents’ eyes. As a parent, it’s a salve to your soul seeing the children’s joy. It washes away anger and eases people’s struggles. Then you no longer want to destroy other people’s lives. With the Street Library, we chase away this ill-feeling.

- “I might see my child playing with yours. They’re enjoying each other’s company. So, how could we keep fighting? You can teach children things, but they can teach their elders plenty of things too.

“On this mat, children find friendship. ‘The Street library has given me the world’, they say. ‘And it’s shown the world I exist too’. Those children who roam the street, when they play on this mat, suddenly they and their games matter to other people. They’re no longer children left to chance.”

This mango tree is like our home

Later in the film, a man describes how ATD Fourth World got started in Central African Republic in the 1980s. Standing under a towering tree, he says,

“It all took off here, under this mango tree. Denis Cretinon [from France] was new to the Volunteer Corps, and very young. Now he’s a big guy, but at the time he was very young. He used to use a scooter to get about. We came here with Charles Ngafo1 and loads of young people.

- “When you see this mango tree, think of it as home. It’s an historic place for the ATD Fourth World movement because it’s where young people first came together.

“There were these young people who earned a living unloading luggage at the airport every evening. However, with our help, they began to see their true value. It was right here that they put together radios on wooden boards.”

“We had plans”, the man explains, showing simple drawings of radio components. “And we put together these radios with salvaged parts. Later we even took those young people to the Bangui University Science Week so they could present what they had made and learned.

Finally, a place of our own

“We shared a lot amongst ourselves under this mango tree. It was right here that children told us what they were thinking about and what they wanted. In fact, it was the children who told us they really wanted to have a place of their own.

“When we constructed the courtyard buildings, they said, ‘Finally we have somewhere quiet to lay down our heads.’ It meant that the police and the older children didn’t chase after them any more. ‘Here, we pull together’, they said, ‘nobody pressures anyone else.’

“So, that’s pretty much how it started, with these children and my friends. Back then, I said to my friends, ‘Let’s teach our jobs to these young people!’”

Family separation

One couple in the film talks about the pain of not being able to bring up their children themselves. In fact, what they describe is a deep suffering that is shared by many families in poverty all over the world. The father in the film ends with words sung like a blues slammer, accompanied by his own stringed instrument.

- “A child is a wonderful thing. I don’t know if one day God will let me see my son again. I play my music to help myself because, when I remember everything we used to do together, it doesn’t do me any good. I don’t know what has happened to our country. It’s in the grip of war and poverty is beyond our control.”

“Refusing to accept that it’s impossible”

Another man in the film recalls the “Zo Kwe Zo” principle, so dear to the people of Central African Republic. “It means”, he explains, “that every man, every woman is a human being. We are all the same species. That’s what Boganda2, the Father of the Nation, wanted to say. There is only one humanity. And it transcends differences, geographic and linguistic borders, and skin colours. We are one united humanity.”

“It’s our ties that are radical”, explains film maker Simeon Brand. “That’s really what’s at the heart of my commitment to ATD’s work. How much experience, strength, and courage the people of Central African Republic must have to create these connections between people, to nurture them in such a difficult context.

“In all the months we spent shooting these films3, certain times really stood out for me, like landmarks. There were times when, all of a sudden, connections seemed impossible.

“Sometimes there are just too many things that divide people. You get the feeling you’ve reached an impasse and certain things are impossible. But these difficult times also pointed out to me where I wanted to go. In fact, my commitment to being a member of the Volunteer Corps starts right there – by refusing to accept that it’s impossible.”

See Simeon Brand’s documentary in French on the Swiss ATD Fourth World website. There you can also find 14 of his other short films, available for purchase in a boxed set.