Education in Burkina Faso: The importance of reconciling both modern and traditional approaches

Burkina Faso, known as “the land of upstanding people,” is often described with unfavorable statistics that do not highlight its strengths. However, it is true that, according to 2004 statistics from UNICEF, it had the second highest rate of school dropouts in the world, only after Niger. In the past decade, enrollment rates have grown from 40% to 79%, but the rate of school success remains low. Infrastructure is a real problem. Even if 100,000 children succeed in earning the primary certificate, there are only 10,000 spaces available to continue schooling. The government is aware of this, and dedicates 16% of the national budget to education. In the past, international aid covered 30% of the education budget, but now it covers only 10%.

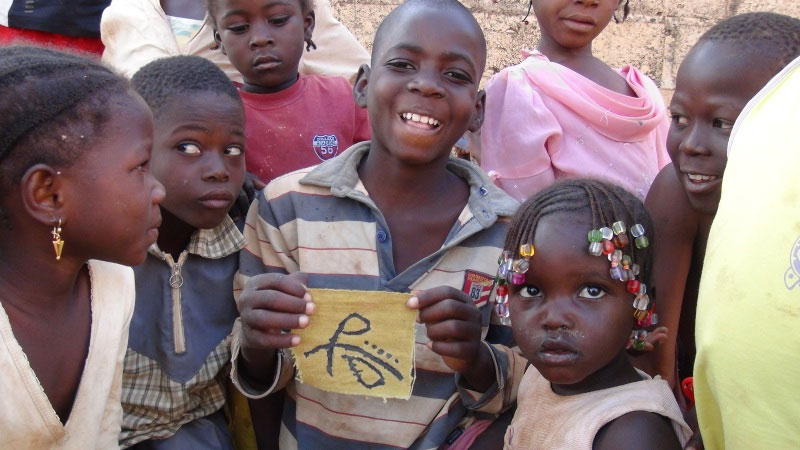

Participants in a seminar organized by ATD Fourth World on education in 2013 identified a strong conflict in the educational system of Burkina Faso, between traditional and modern approaches to education. This disconnect exists in other African countries as well. Out of a population of more than 16 million people in Burkina, about 80% work in the primary sector, mainly in agriculture and animal husbandry. (This is compared to 16.4% in the service industry, and 3.4% in manufacturing.) Despite efforts from various stakeholders, the education system does not manage to adapt itself to the aspirations and rhythms of the local communities, especially in rural areas. This means that for children to acquire agricultural skills, they are forced to miss school during the planting season. In the Fula population, the children who wish to acquire the skills of breeding cattle from their families or their community need to temporarily leave school as these skills are not integrated in the curriculum.

Below: Fatimata Kafando talks about how her parents gave her the courage to go to school and learn despite the humiliations she suffered due to the poverty they lived in.

Play with YouTube

By clicking on the video you accept that YouTube drop its cookies on your browser.

In this context, the necessity to reconcile traditional education with modern education seems clear. As a Burkinabé father living in extreme poverty said: “The future of our youth is in agriculture and livestock.” The African Union has made the recommendation to African countries to take charge of their educational programs and strategies instead of depending on donor strategies, which often offer help designed to achieve goals foreign to the continent. In fact, foreign aid should align itself with targets set by each country. These objectives, according to recommendations from the African Union, should take into consideration the cultural heritage of each country.