Forging Solidarity: People in Extreme Poverty Act for Change

In the video below, ATD Volunteer Corps member, Diana Skelton talks about the chapter she and Martin Kalisa, ATD’s Regional Co-Director for Africa, co-wrote for a recent book entitled Forging Solidarity. In the video, she talks about:

- ATD’s “solidarity, not charity” approach

- The difference between poverty and extreme poverty

- Merging Knowledge, a methodology for participatory research that enables academics and people in poverty to discuss issues on an equal footing.

Play with YouTube

By clicking on the video you accept that YouTube drop its cookies on your browser.

More videos can be found on the YouTube channel: Popular Education South Africa

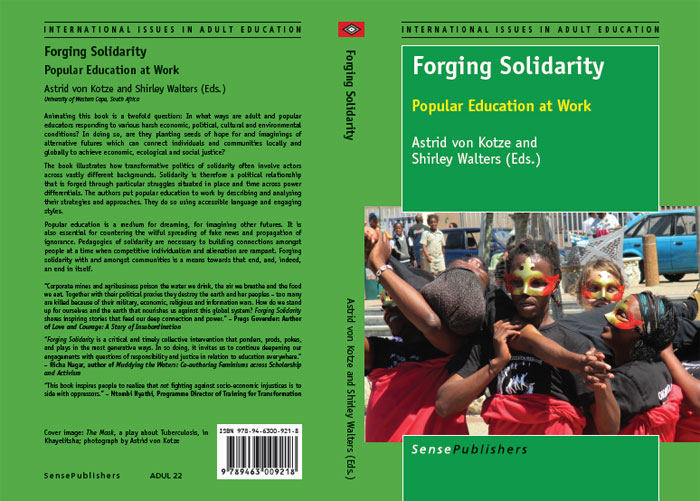

The chapter, “People in Extreme Poverty Act for Change” appears in Forging Solidarity, Popular Education at Work. The authors of the book define popular education as a “theory and practice of education directed towards promoting social change rather than social stability. It is rooted in the real interests of people committed to learning and acting together towards a fairer and more egalitarian society.” Below are excerpts from the chapter.

Solidarity, Not Charity

[ATD founder] Joseph Wresinski (1917-1988) grew up in poverty and exclusion. He was born in a World War I detainment camp for enemy citizens where one of his sisters perished of malnutrition. When he was growing up, his family was stigmatised and insulted by others. He recalled, “Contact with others was based on charity, not friendship. From my earliest memories, the lack of money was linked to shame and violence.”

Wresinski described his childhood memories of receiving charity as a trap: people who offered his mother charity not only embarrassed her, but judged and constrained her, even urging her to abandon her most troublesome son in an orphanage. In developing an approach to solidarity, Wresinski’s priority was always to increase each person’s freedom. He was always demanding of people in extreme poverty, calling on each one to try to live up to their highest ideals. He expected them, in turn, to exercise their freedom by becoming demanding of themselves and of others, insisting on respect, and challenging the top-down nature of charity. His view that care and support for individuals were also political acts led him to continually connect such acts with calls for policy changes. Today, connecting the personal to the political remains a centrepiece of ATD’s advocacy at the UN.

What’s the difference between poverty and extreme poverty?

Within low-income communities, there are always some people whose situation is even more difficult than that of their neighbours. They may be looked down on and disparaged by others. … In an urban slum in Spain, a woman says, “When I go through rubbish looking for food, neighbours tell me I’m making all of us look bad. But what do they think? That I enjoy doing it? […] We’re poor so we don’t think of anything but tomorrow. Thinking about how to get the next day’s bread stops us from thinking any further. From the minute you wake up, if you can only ask yourself, ‘How can I manage today?’, you can’t think of anything else.”

In any low-income community, ATD’s priority is to seek out the people whose lives are the most heavily burdened, particularly those who are ignored or stigmatised by others. Unless people who know what it feels like to be left out or pushed aside are the ones designing a project, it will never reach everyone. So ATD’s aim is to think together with people in persistent poverty before beginning any project in order to ensure that no one will be left behind, and to benefit entire communities.

Merging Knowledge

People in poverty have knowledge that is ignored by others. Wresinski accused academics not only of exploiting and subordinating people in poverty, but also of having “up-ended or even paralysed the thinking of their interlocutors. This happened because [researchers] did not realise they were dealing with a thinking that followed its own path and goals. […] Paralysing the thinking of the poor [happens when research] is for a goal external to their life situation, one they did not choose, and which they never would have defined in the same way as the investigators.” ATD developed Merging Knowledge (MK) to change this, challenging the politics of knowledge by asking: Could the thinking of people in poverty about their collective struggle somehow find its way into the university system?

A professor of criminal sociology who took part [in MK work], Françoise Digneffe, explains why the academics had to take a back seat to people in poverty, and how MK challenged her own academic work:

Our approach was to produce something about the vision that people in poverty may have of society; therefore it is only for people in poverty to say what they think. What we can do is to work with them so that they can express their thinking in such a way that it can be more understandable. […] It’s our job to ask questions—but we had to make them understand that our questions didn’t mean we didn’t believe them, or that they were lying. […] I question more than ever the presumption that we can understand what people are saying better than they understand themselves. […] Academics, like many people, have doubts and fears about the environment in which people experiencing poverty live. […] This whole experiment makes you question the meaning of the words that we use. […Now], I’m of the impression that I use these complicated words that won’t be understood as a kind of windshield so that I don’t even have to see. This intellectual jargon […], maybe we don’t really know too well what it means. When we have to use words which seem simpler, we really have to start thinking.

Download the full chapter as a pdf.

More information on Forging Solidarity.

More information on ATD’s Merging Knowledge methodology for participatory research.