How Can Women in Poverty Challenge the Patriarchy of Social Services?

In 2017, ATD Fourth World invited people around the world to document real-life “Stories of Change”. These stories are about situations of injustice and exclusion caused by extreme poverty. Written by activists, community leaders, and others, they show that when people work together, real change can happen.

More about “Stories of Change”.

By Diana Skelton (UK)

“In the two years I was homeless, the main thing that was reinforced within me was that I was not worthwhile, that I did not belong, not only to the community, but maybe even to humankind.”

-Zenobia Embry-Nimmer

“Homeless families have to attend meetings on parenting, budgeting, and nutrition. I found all of the above insulting. To me, it was simply more reinforcement that I was a failure and that being poor implied that I was not intelligent or a good parent. […] The abuse of power was perhaps the most disturbing part of my experience and has left the deepest and longest lasting scars. […] I humbled myself and felt humiliated many times for the stability of my children.”

-Brenda Farrell

Like Zenobia and Brenda, many women living in poverty in wealthy countries continue to have devastating experiences with social services. Intended for support, these services continue to be designed from the top-down, without meaningful dialogue with the families in crisis who depend on them. When you meet women in poverty in the US, the UK, France, Switzerland, and similar countries, their treatment by social services is consistently their top concern. And yet, at the September 2015 UN conference on women’s rights in Europe and North America, this issue once again remained unheeded.

The conference was part of efforts in each region around the world to take stock of both progress and setbacks in the two decades since the historic 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing, China, when heads of state agreed that “women’s rights and gender equality are central to the world’s attainment of equality, sustainability, development, and peace.” Fighting poverty was built into the Beijing Platform for Action — but the objectives chosen to address poverty were only economic. As important as it is to eliminate gender bias in the labor market, and to ensure equal access to income and credit, this is far from enough. The feminist movement that led to Beijing challenged patriarchal structures to become participatory. But this has not transformed the power structures of social services.

Dr. Donna Haig Friedman, director of the University of Massachusetts’ Center for Social Policy, observes: “We, with more ample incomes and less challenging life circumstances, assume that we know what homeless parents need to do to make their lives better and presume to speak for them in our advocacy and policy-making efforts. In fact, as evidence suggests, our condescension and good intentions may not only be off the mark but also may have extremely detrimental effects on the very parents and children we are trying to help.” Friedman’s words are about her research with mothers and staff in five emergency housing shelters. While some shelters manage better than others to be sensitive to the needs of the families they serve, now almost fifteen years later, many families in poverty face the same challenges shown in her research:

- A requirement to separate men and teenage boys from other family members in order to receive shelter;

- Very little or no privacy from staff and other families;

- No autonomy for parents to make decisions about their children’s meals, hygiene, or leisure activities;

- Patronizing, and sometimes degrading, treatment by staff that can add to tensions within families.

While the concerns of women like Zenobia and Brenda were not able to influence the recommendations of the September 2015 conference, they have influenced professionals in the fields of social service and human rights in Luxembourg, several of whom have joined their voices to those of people in poverty in a new book sharing the challenges of raising children despite poverty, and their vision and hopes for a way forward.

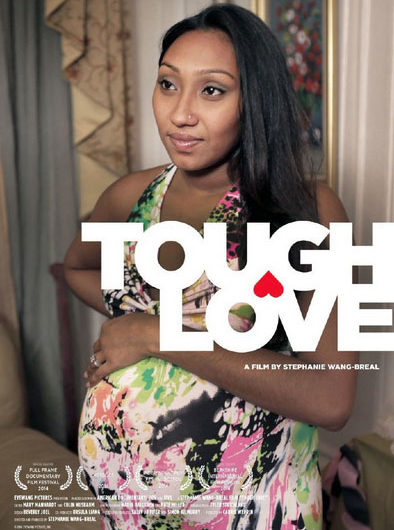

The concerns of women in poverty have also influenced Emmy-nominated filmmaker Stephanie Wang-Breal. After making a film about families adopting children, she discovered that many foster parents in the US “didn’t want her to talk to birth parents.” She dug further into the child welfare system and made the film “Tough Love” about two birth parents “fighting poverty and prejudice to put their families back together.”

In the international context of the UN, it can seem as though concerns about the ways social services are provided are relevant to only those countries whose governments can afford them. But this is shortsighted for two reasons. First, because more and more non-profit agencies based in those countries export them around the world. Private social workers in the Philippines have sometimes removed children from their parents’ custody simply because of their insecure housing. The second reason is that “we the peoples” of the United Nations remain divided between “donor nations” who are rarely criticized because their funding is needed, and other countries that can be categorized as “least developed” or “highly indebted and poor.” Ignoring the way that social services in “donor nations” have too often damaged the very people they are intended to support is the utmost hypocrisy. Innovating ways to reverse that damage will require drawing on the intelligence and expertise of women and men in poverty in all countries.