Learning from People in Poverty

In 2017, ATD Fourth World invited people around the world to document real-life “Stories of Change”. These stories are about situations of injustice and exclusion caused by extreme poverty. Written by activists, community leaders, and others, they show that when people work together, real change can happen.

More about “Stories of Change”.

This story describes the beginning of a participative research approach using Merging of Knowledge with populations in situations of extreme poverty.

By Francoise Ferrand (France)

In 2000, a group of academic researchers, ATD Fourth World Volunteer Corps members, and activists with a lived experience of poverty came together to discuss civic engagement. The meeting was part of an ongoing research project conducted with the Merging of Knowledge research approach.

Merging of Knowledge is a research technique that seeks to create spaces where people in poverty can openly share their thoughts as equals with researchers. By breaking down the sort of unequal relationships between researchers and subjects that traditionally define academic work, Merging of Knowledge opens up all those involved in a project to new perspectives.

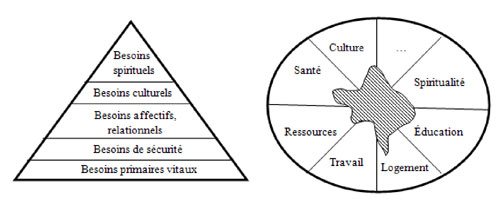

In this discussion, the theme was the essential needs of all human beings. A housing professional talked about of the hierarchy of people’s needs that must be respected, closing her presentation by referring to Maslow, an American psychologist. The activists and I, who co-led the group on participation, had never heard of Maslow. I asked for an explanation. A specialist then drew Maslow’s “Pyramid of Needs” on a board. Along with the activists, I discovered Maslow’s ranking of needs in a hierarchy along with the principle that one cannot access the next level if the needs of the lower levels have not already been met.

Carine, Patricia, and Baudoin reacted in the same way as Joelle, who said,

“I lived in a slum outside the village but I still needed to listen to classical music in order to keep going”.

An animated debate followed on the place and importance given to people’s needs and who defines them.

A professional in charge of a Community Centre for Social Action had earlier explained that his town provided housing to all people who had no home. The professional explained how, a short time after being rehoused, one of these people, aged around 40, was found dead in his apartment. “He died decently”, concluded this professional. The activists, however, raised questions: “Right, he had a home. He was off the streets, but had we really taken into account this man’s needs?”

For Carine, Patricia, Baudouin, and Joelle, people’s needs cannot be divided up as neatly as Maslow would have it. They stressed the importance of seeing each person as a whole, not only seeing what the person lacks, but also their aspirations.

It often seems that people only consider essential the primary needs of those living in poverty. “A person may have cultural needs even if they doesn’t have any food or a home. It’s sometimes the only thing left they can hang on to”, the activists said.

Joelle explained:

“My daughter doesn’t care about sleeping in a bed because, instead of buying a bed, she prefers to use the money for her horse riding lessons”.

Patricia quoted Genevieve Anthonioz de Gaulle, President of ATD Fourth World at the time. During the Second World War, Genevieve was in the Ravensbruck concentration camp. “She told us that, deprived of everything, it was culture and spirituality that had helped her to hold out.”

At this point in the debate, I suggested that the activists use the board to present their way of seeing people’s needs. The pyramid became a circle divided into parts, with a need written in each part, in no particular order (health, culture, resources, housing, spirituality, education, work, etc.).

The community centre professional then suggested that this diagram become an evaluation tool for both the person who has needs and the professional. “In that way, the person may be relatively happy with their housing, but worried about their health, their children’s schooling, or their work.”

The pyramid turned into a circle is now taught in a number of social worker training institutes. In addition, over the years the findings of the Merging of Knowledge and Practices experimental research programmes have resulted in a number of training programmes in other professional institutions.

There is also an increased interest in the academic world in participative merging of knowledge research programmes that take into account the knowledge and experience of people facing extreme poverty.

More about the Merging of Knowledge approach.

How Merging of Knowledge was used in ATD’s 2016-2019 Dimensions of Poverty Research.