“Living in a Welfare Hotel Is So Embarrassing!”

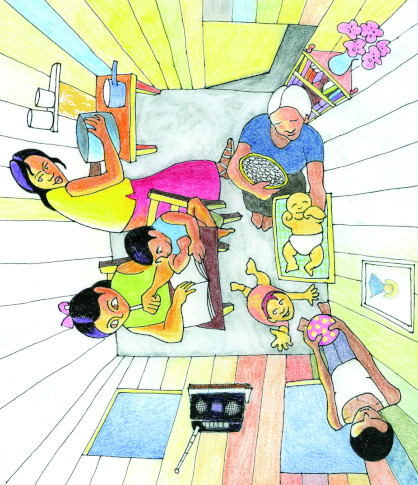

Image: Lockdown in Peru, 2020 © François Jomini/ATD Fourth World

Profiting from poverty

Welfare hotels are generally considered to be a terribly inefficient way to house people in poverty. Nevertheless, France has dramatically increased their use according to a new article by sociologist Erwan Le Méner. As a result, poverty hotels appear to be a growing business opportunity in the country.

In France’s complex emergency housing policy, Le Méner explains, welfare hotels operate in tandem with other emergency facilities such as centres for asylum seekers. More and more, public and private organisations are using these hotels when no other options are available. Refugee centres, local governments, and other entities will simply send off families and individuals to these low-end hotels, often for an indefinite period of time.

ATD Volunteer Corps members experience life in a welfare hotel

To learn more about life in a welfare hotel, two ATD Volunteer Corps members became involved with different hotels near Paris. For a year and a half, Carine Parent lived in one six-story building. Over a nine month period, Angela Ugarte regularly visited approximately 40 families living in a three-story hotel. While some of the families Carine and Angela met had come to France only recently, others had been there for several years.

Little by little, both Volunteer Corps members got to know residents in the two hotels and saw many aspects of the harsh life they endured. What struck Carine and Angela the most, however, was how neighbours within the hotels made friends and helped each other out. When you live in grim cramped spaces every day and you don’t know how long it will last, friendships are what make life tolerable.

Daily life

In Carine’s hotel, there was one tiny shared kitchen on the sixth floor. Equipped with just two hotplates and a microwave, the kitchen was the only place families could cook or gather together.

On the first few floors of the hotel, there lived only young people and single mothers with small children. Carine noticed that these single mothers often stayed in the hotel for only a few weeks. However, families with school-age children remained longer.

Most of the young people on the lower floors had only recently come to France. As “unaccompanied minors”, they were supervised by the French government’s social service program for children. In this hotel they didn’t dare go up to the kitchen on the sixth floor to cook their meals.

One day, Carine discovered why. A few young people had asked her to read a letter they had just received. So she invited them up to her floor. Immediately, one of them said:

- “I can’t go up to that floor! People will think I’m going to steal something or attack someone. I can’t go there–that’s the family floor!”

In both hotels, residents are under constant surveillance. In the kitchen and many locations on each floor, cameras see everything. “It’s suffocating!” exclaimed Angela.

Food and work are both scarce

In the hotel Angela visited regularly, the top floor was reserved for people who work nearby. The lower two floors were for families waiting for visas. Among these, some have been living in the hotel for three to five years. The parents work mainly in the building, cleaning and baby-sitting. Most of them are not officially employed, but paid under the table.

Rather than cooking in the kitchen, young people use vouchers from the government social service program to buy a meal at the local kebab or pizza shop. In the morning, they eat standing up in the lobby where they can get a a cup of coffee to go and a small pastry or cookie. For some, these are the only meals they have all day.

The 40 families in Angela’s hotel share eight hotplates, not nearly enough for everyone who needs to cook. This makes life complicated and causes daily conflicts. To deal with the shortage of space and cooking facilities, some families start preparing food in their room. Then they queue up to do the actual cooking in the kitchen.

In addition to the minimal cooking space, the bedrooms are extremely small. Yet some mothers stay shut up there all day with their children. Because the hotel is located in an isolated industrial area, there’s no place outside for children to play or just get some fresh air. Fathers generally spend the day working or out looking for a job.

During the pandemic lockdown, families were not allowed to leave their rooms, making it very hard to meet even the most basic needs.

“Living in a welfare hotel is so embarrassing!”

Whether they are living alone or with others, the young people at the hotel associate their address with shame. “Living in a welfare hotel is so embarrassing!” they often say.

In Carine’s hotel, one couple has been living with their two children for more than twelve years. The youngest child, now 11, has never known any other kind of life. One day, the mother told Carine how angry she is about this.

“I don’t understand”, she exclaimed. “Living in a hotel is expensive! If we had an apartment, I could cook for my children. We could be a family!”

Cramped conditions with little privacy

In the hotel she visited, Angela saw how difficult it was simply to move around in the tiny hotel rooms. Even with a very few pieces of furniture, they were terribly cramped. A bed had to serve as a desk for homework, a table to eat on, a sofa, and whatever else the family needed.

When one mother managed to find a small table for her daughter’s homework, she was told to remove it immediately. “It’s against the rules”, the hotel said. So the mother got a medical order stating that, for health reasons, her daughter needed to do her homework sitting properly at a desk. Still, the hotel manager refused to let them keep the little table. Mother and daughter could do nothing but accept this repeated humiliation.

In this particular hotel, some bedrooms had showers but others didn’t. When bathrooms were communal, some parents were afraid to let their children use the restroom or shower alone in the presence of strangers.

A strong community

In the hotel where Carine lived, most of the families on the top two floors have been there a long time. Even though they always say how tough life is, the neighbours have still managed to create a strong community. Confined together day after day, they are always finding various ways to help each other out. In the small kitchen, the women sometimes cook together or teach each other recipes. One woman collects unsold bread from the local bakery and distributes it to young people who have no family or to other residents.

One day, Carine took a neighbour who was pregnant to the hospital to give birth. When Carine returned to the hotel, she showed everyone a picture of the new baby. Thrilled for the new mother, the families all celebrated the baby’s birth. “It was a real party”, Carine recalls. “It was wonderful”.

Shortly afterwards, the new mother developed health problems and couldn’t always take care of her baby. Immediately, the other women in the hotel leapt into action. Asking the older kids to look after the younger ones, the women took turns helping out. They gave the new mother advice about bathing and infant care. One neighbour even managed to buy prescriptions the new mother needed.

A common struggle

While France has said it wants to stop using such unsuitable hotels, they are still a common form of housing for families in poverty. Surprisingly, for many hotel owners, taking in families in poverty pays better than their traditional hotel business. So well, in fact, that other entrepreneurs are getting in on this business as well.

Society has always found ways of segregating people in poverty by herding them into certain buildings or areas. Now immigrants living in these hotels or on the street gradually sink into extreme poverty. They too echo what people of the “Fourth World” have long experienced. Yet both groups aspire to be recognised as full citizens. They want to be heard and to be a part of “normal” society just like everyone else.

More information on ATD Fourth World in France

ATD Fourth World France’s website

More information on ATD International’s work on housing