My People Are My Strength

My People Are My Strength (Les Miens sont ma force) by Martine Le Corre, was published at the end of 2023.

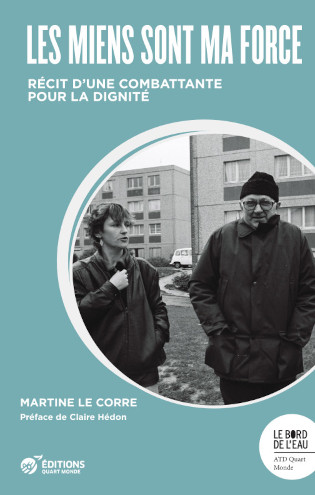

Martine Le Corre grew up in a housing estate in the suburbs of Caen, France, in a family of 14 children. In the mid-1970s, when she was barely eighteen, she was torn between wanting to fight for her right to happiness and giving in and just taking life as it came. She was exhausted by the hardship she experienced. That’s when an unexpected encounter changed everything.

Meeting ATD Fourth World founder Joseph Wresinski and the other ATD Fourth World Volunteer Corps members was a turning point in her life.

Today, she works with them to overcome extreme poverty and shares their belief that those experiencing poverty can themselves become activists and work on the side of those who are most vulnerable.

She was previously involved in the Merging Knowledge research project and the team which grew out of it, as well as the team for the research initiative “Extreme Poverty is Violence – Breaking the Silence – Searching for Peace” and the team responsible for improving ATD Fourth World’s governance. She then joined the “Support for Commitments” group.

Her presence in France helped her to build strong ties with her community. Martine ran the People’s University in Caen for several years before joining the International Leadership Team from 2017 to 2021.

Though the beginning was not easy, Martine came to find that overcoming fatalism is a battle, and it cannot be won without those who are the most affected by poverty: those like Martine, her family and her community and people.

My People Are My Strength is the story of a life of passion, commitment, and liberation, an effort to change society and see those living in poverty can lead the battle against it.

Extract from the book

There are words which honour and uplift you: “capable”, “intelligent”, “interesting”, “creative”, and “sociable” … And there are others which put you down, defeat you and destroy you — like “misfit”, “ill-adapted”, “asocial”, “scum”, and “good-for-nothing”. And it’s the latter that shaped the person I was and the people around me. We experienced exclusion, humiliation, ostracism, judgement, rejection, shame, and contempt.… Every one of those words impacted our lives and our history. I accepted what others thought of me and internalised their words, believing my life wasn’t worth much. I lacked the words to call out injustice, the words to denounce, the words to defend myself.

Since then I have of course, caught up. After encountering ATD Fourth World I have dared, spoken up, listened, denounced, demanded, expressed, chosen my words carefully, reflected, and learnt to believe that I am “somebody” and that my background is an asset.

As part of ATD Fourth World, I have discovered the intelligence, solidarity, and wisdom of lived experience.

These words resonate with me now, and I have found that these words can be put into action.

Interview with Martine Le Corre

What inspired you to write about your “path of commitment — strewn with pitfalls” — as you describe it?

The idea to write came about in collaboration with Joseph Wresinki, the founder of ATD Fourth World. Every month or so, I went to see him at Méry-sur-Oise. We had long discussions about various subjects, and we intended to write a book together. We didn’t have the opportunity to see it through, though. After his death in 1988, I thought about returning to the ideas we had discussed, but I wasn’t satisfied with the initial result.

What really resonated with me was discussing the idea of commitment and the ways it can change someone’s life. I dreamt of writing a book with others, but I couldn’t make it happen. So I set about it by myself. In this book, I have tried to retrace the defining moments of my journey and to be as honest as possible. I hope it will be seen as an invitation for discussion, one that inspires deep conversation.

ATD Fourth World activist

In this book, you describe your path to becoming an ATD Fourth World activist. What is activism to you?

It’s a commitment to and with others. Becoming an ATD Fourth World activist means seizing the opportunities to change your life and connecting to others with similar experiences. Activism is this profound connection to your community, to those in extreme poverty; it’s something you experience with them. And it’s this connection that transforms your own life. It’s also very demanding because, first and foremost, you have to take a good look at yourself; you have to look at what you need to change in yourself and to live up to the ambitions you dream of for others. It allows us to be an actor of change in our own life. Being an activist has given me a lot of strength.

The word “resistance” appears repeatedly in the book; what does it mean to you?

It’s clear that those living in poverty are the real “resisters” in the face of a life which has been forced upon them. It is incredible to see the situations in which people in poverty survive here and across the world. They have to resist everything that society throws at them. Resistance works on many levels: you have to resist those who provoke you, those who constantly ask you to prove yourself, and those who ask, “Who do you think you are?” again and again when you have the slightest success. And you also have to resist yourself: the little voice that says, “You don’t have a place”, “you are fooling yourself.”… It’s very painful. My life hasn’t been a calm rolling river. I’ve moved forward, backwards, then forward again. There’s no denying any of that.

ATD Volunteer Corps members

You talk about the role that the ATD Volunteer Corps members have had on your journey. What role do they have in ATD Fourth World?

It’s a cornerstone. I’m a great believer in the Volunteer Corps. Nowadays, I expect and demand a lot from members. We need people who are not in the process of “finding” themselves. We need people who are convinced that extreme poverty is a serious form of violence and who are ready to commit themselves on a daily basis to working with families living in it. This means confrontation, letting yourself be challenged, and continual critical interrogation.

In the book I cite the story of Mr Alexandre, an activist from Burkina Faso. He reminds us that ATD Fourth World also enables those who do not live in extreme poverty to change how they view people who do, to transform themselves, to be enriched and sometimes to see their lives change. However, for those living in extreme poverty, it’s harder for life to change. So they’re the ones we need to be with; that’s what volunteers must prioritise.

At the end of the book, you say, “I think, today, that we could be more daring”. What should ATD Fourth World dare to do?

Dare to shake itself up more, to say no, to question others and ourselves. Dare to do real advocacy and provoke fundamental changes. We must dare to denounce, confront more politicians, and question our partnerships, making sure not to forget that our most important partnerships are those with people in poverty.

I want everyone in ATD Fourth World to learn from each other’s experiences… Let’s dare to do more!