Memories I Can No Longer Silence

By Guendouz Bensidhoum, ATD Fourth World Volunteer Corps member

“Memories I Can No Longer Silence” and “The Roles We Play” were two striking exhibitions by Guendouz Bensidhoum in late 2022. Both took place in Créteil, France where the artist grew up. Here, the ATD Volunteer Corps member eloquently describes three of his paintings.

No choice but to break the rules

These paintings depict the lives of people in the neighborhood where I grew up, a transit estate1 just 13 kilometers from Paris.

As I child, I remember how neat the lawns were. In the middle of each there was planted in the ground an enameled sign. “Lawn out of bounds. Anyone walking on the grass will be fined.” If we threw a ball too far and it landed on the lawn, the caretaker’s whistle would interrupt the game.

When someone hung washing at the windows, there was the threat of a fine too. This was how they tried to impose order on families who had no choice but to break the rules. How could you not play ball in the courtyard when there was nowhere else to play? How could a family of six to eight people dry their laundry in buildings too small to have a utility room?

Hopes and dreams, doomed to failure

My parents were immigrants who always planned to return home to Algeria. When they had enough money they would go. Most important, after their children were educated they would go. They would go when each child had the “Certificate of Professional Aptitude” that could support Algeria’s development and help them re-integrate there.

It was an illusion. Like most immigrants, our parents had to resign themselves to abandoning this plan. In the meantime, school in their eyes was the symbol of success. It meant so much because, like almost all adult immigrants in the neighborhood, they themselves could neither read nor write.

From 1962 to 2018, the so-called “transit estate” became a permanent home for many families. I lived there until 1984, when I was 24 years old. But my mother and sister didn’t leave until 2002, after living there for 40 years.

A waste of youth

After so many years on that estate, I’m still angry as a victim of–or witness to–so much injustice and humiliation.

- It started in school, which should have been a place of opportunity for all of us. In the end it was only an opportunity to go somewhere no one wanted to be, or sometimes to go nowhere at all.

There was such a terrible waste of youth left to their own devices. For something to do, they killed time hanging around the shopping centre, that temple of consumerism. They always hoped for some promising opportunity, maybe being hired as a warehouse worker or a cashier for the women. And when something didn’t turn up, there was nothing left but despair or just getting by. And then, inevitably, people had to accept the unacceptable.

- In my memory, I see the faces of so many boys and girls condemned to be treated with contempt because they were born into an impoverished and destitute family. I remember so many young people gone too soon because of drugs, alcohol, or illness.

- For me, they were victims of a double misfortune. First, they were born into poverty. Second, so many programmes claiming to be “for the benefit of disadvantaged youth” never in fact provided them any support.

A different approach to poverty

I still hear words that ATD founder Joseph Wresinski spoke in 1987 on the Plaza of Human Rights at the Trocadero in Paris.2 He was talking about us! Wresinski evoked our courage and our desire to be useful, to love and be loved.

In 1956, at the request of his bishop, Wresinski had joined families living in a shanty town called Noisy-le-Grand. There, just outside Paris, he found destitution that reminded him of his own family’s experiences in Angers, France. Gradually, Wresinski and those deeply impoverished families built the ATD Fourth World movement. Today, this international movement sends Volunteer Corps members to work alongside the most disadvantaged and marginalised families on every continent.

Capturing more than words can express

In 2015, I realized that through painting I could bear witness to the experience of people like us. At that time, I no longer had the words or the will to talk about the unfairness of their mangled lives, which I found utterly unbearable. Yet faces that I just couldn’t forget kept coming back to me.

I was gripped with the desire to paint my neighbourhood. Perhaps other people could learn about these unexpected stories. Maybe some would remember people living in poverty that they saw daily without ever knowing or understanding their lives, who knows?

I built scenarios impossible to articulate with my words. Only the magic of colour would help to express them. This work kept me busy for six years.

“These paintings would be large”

Painting allowed me to see the extent to which I existed differently in the eyes of others. And it brought me recognition, a validation of sorts.

My approach is always connected to memories of things that left a deep impression on me. I remembered tough times and violence but also happy memories, moments of joy shared with my friends and neighbours.

It very quickly became clear that these paintings would be large. I didn’t want them relegated to the end of a corridor leading to the restrooms or some out of the way nook.

An ensemble of three pictures

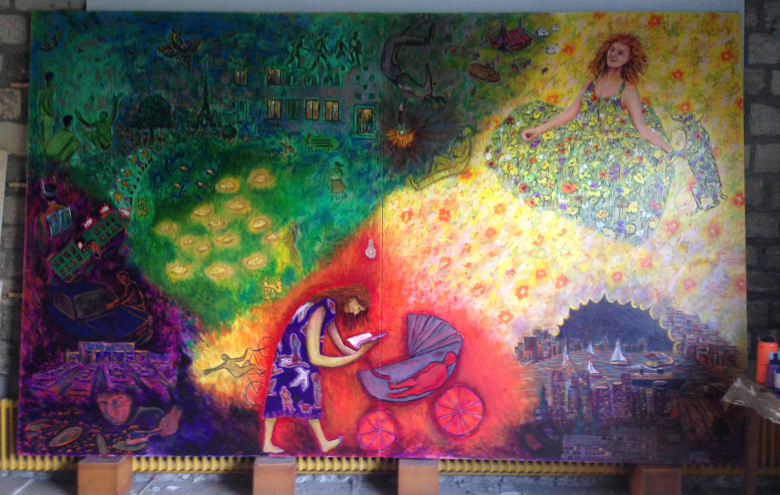

The first painting evokes my childhood and friends from that time. When I was painting it, I realized that this image honours the girls and women who struggle to keep their family together. I painted for these child-mothers deprived of their youth. And in childhood, there is school, of course, but also friends, games–in short, life!

The second picture talks about adolescence and becoming an adult. For me, it was a difficult time with drug-related violence, unemployment, and a sense of uselessness. Along with all this, there was the experience of exclusion from the city and the outside world. However, for me adolescence became the time I discovered love, dreams, studies, and travel. Yet this was a fate from which most of us were barred by that exclusion from the world surrounding us.

Sadly, some people left us far too soon, victims of this violence.

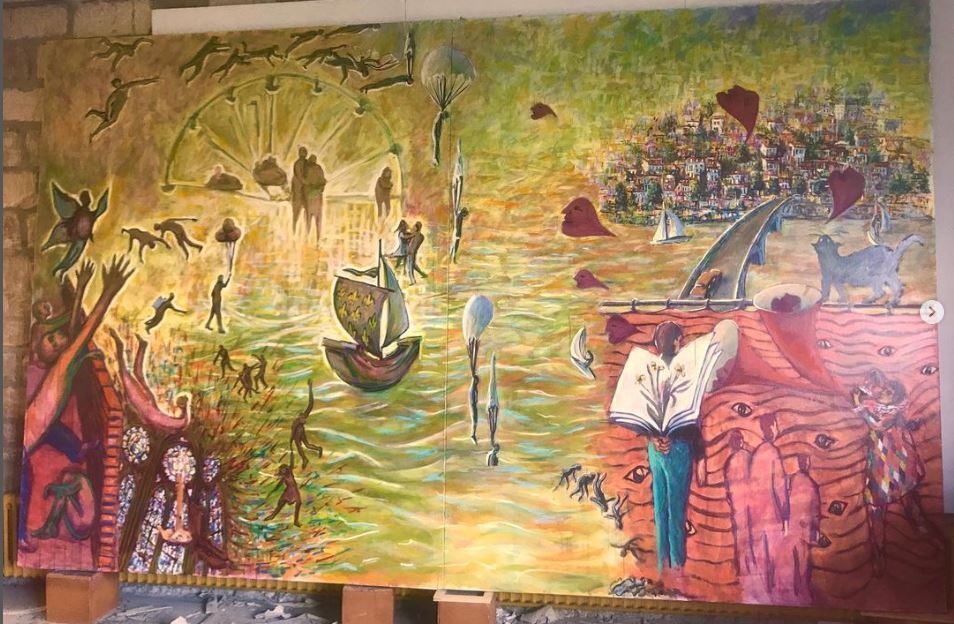

The third picture shows us a people, excluded yet never losing hope that we could improve our lives through hard work. A few did manage to integrate, but for almost all, their past caught up with them.

Yet even while the city remains closed off, they continue to look for a place they can call their own.

- Very often, despite their tenacity, they stay where they are, taking almost no part in the city’s life. And society doesn’t want to see them. Others don’t understand these people and wish only to never run into them again.

An invitation into an unknown world

These paintings do not claim to capture all the facts. Yet certainly they bear witness to the unacceptable, to violence. But most of all, with their colours, they seek to welcome you into an all-too-unknown world where people enamored with humanity aspire to more friendship and more love.

Guendouz Bensidhoum describes painting in the Appalachian region of the United States