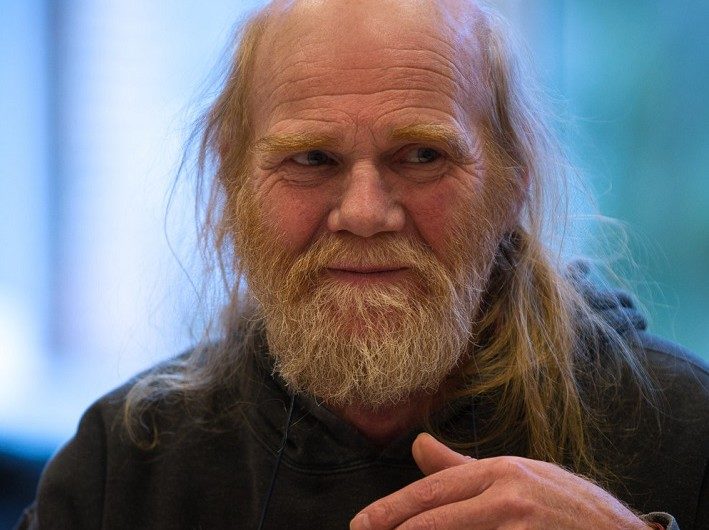

Patrice Bégaux, Activist for Europe

“We must go beyond reciting facts and reach out to everyone, because time is running out and it’s always the same people who suffer.”

Belgium — Since 2004, Patrice Bégaux has participated in ATD Fourth World’s projects in Tamines, 70 km south of Brussels. His desire to meet people and his kindness toward them have always been guiding forces in his life. On 5 March 2014, he took part in a Fourth World People’s University session held at the European Parliament.

“Life is complex,” Patrice said as he looked at photos from that event. He had put time and energy into the gathering for more than a year, from attending preparation meetings to drafting final proposals. As he answers questions, his soft voice offsets his penetrating gaze. “Many of the participants have led a hard life, and they still have difficulties. I’m living on a minimum income, but I have an easier life today than I did before.”

With the upcoming European elections, Patrice sees this meeting at the parliament as a chance to make important points. “I am not the type of person who gives compliments. They want to reduce poverty in Europe by 20 percent by 2020. It’s ludicrous to start off with that kind of goal — we don’t just need to reduce poverty; we need to eradicate it, destroy it. It shouldn’t even exist. Finding some stop-gap measures doesn’t interest me. We shouldn’t be aiming for 10 percent, we should aim to have no people in poverty. If the proposals aren’t enough to overcome poverty, we shouldn’t be afraid to consider what is actually working in some countries, for example, a programme in Luxembourg called Second Chance, or the education systems in Scandinavia.”

“I just did what I could with what I had”

Patrice has lived for the last ten years in a region that has suffered deeply from Belgium’s centralisation. “Before, there were thousands of people who passed through the train station, but now there’s no more work to be had here.”

Patrice knows something about job-hunting. “When I was young, I was constantly on the move. Instead of seeing that as an advantage, employers saw it as a sign of instability. Today it would be the opposite. The world is weird sometimes.” Patrice has worked with electricity and pottery; he has been a shopkeeper, a scrap merchant, and a youth hostel manager. “It made for a creative life. When you meet different people, you become richer from it.”

Working in a biscuit shop brought stability to Patrice’s life. “We started with only two of us: the boss in his office and me in the workshop in the basement.” After twenty years, the business had ten employees. “I hired a lot of people who had problems: former prisoners and alcoholics, for example. If I hadn’t given them a chance, I don’t know who would have. I just did what I could with what I had.”

But health problems forced Patrice to stop working. He left Brussels and settled in Tamines. The troubles he had known as a child caught up with him. “During my life, I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor, but extreme poverty always haunts you.” At a food bank one day, Patrice met a member of the local ATD Fourth World group who invited him to participate in People’s University meetings.

All his life, Patrice had been mindful of other people — he hadn’t waited until then to get involved. But with “this group of people who have experienced the same things and who stand by one another”, he saw an opportunity to take action. It’s been ten years now since Patrice joined the group. At times, he only just managed to get through difficult situations, one time thanks to a judge who chose not to condemn a house he had just moved into. “She knew that I would never find anywhere less expensive and she took this into consideration. That is what we look for in ATD Fourth World: that professionals take everything into account when they’re making important decisions about other people.”

Patrice continues to offer support to many people. “He’s always so sensitive in taking care of others,” said a friend. “People know they can count on him at any time. They trust him, and that makes them feel better.” For Patrice, helping someone allows him to see things differently. “Seeing the positive encourages people to start moving forward.”

Everything starts with school

The question of education was also discussed during the European Parliament meetings of 5 March. “Everything starts with school. People in poverty stay in their place and schools continue to make other people excluded: people who leave school without training, without work, without any kind of pride.” Patrice has bad memories from his time at school, where he was taunted for being different. When he was 4 years old, he saw a gate left open, and walked away from school for the first time. That has marked his life since then. “I didn’t finish elementary school. I must be stupid somehow, or maybe there was another reason — I prefer the second theory.”

It disturbs Patrice that school is the opposite of the real world: “You’re forbidden to look at your classmates’ work, but when you’re an adult you always have to compare things and work with other people. It’s not logical. There are other teaching methods. School should change completely. We should speak there about the future, about communal life, about sharing.”

During this People’s University session at the European Parliament, Patrice was particularly struck by discussions with people who work in institutions. “We were able to meet and talk together, even though if they had met me on the street, they probably would have crossed to the other side to avoid me. The people who were there were interested in what we had to say. Now we have to find ways to reach out to people who weren’t there. No matter what field people work in, there is always a link with poverty. Through the laws they enact, politicians are always accountable for people’s situations. We must go beyond reciting facts and reach out to everyone, because time is running out and it’s always the same people who suffer.”

— From an interview done by Thibault Dauchet