Solidarity, Mutual Support and Resilience

Painting above: © Guillermo Diaz 2020

By ATD Fourth World Latin America

Over recent months, ATD Fourth World has created virtual spaces for conversation in which people can reflect together on the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. The conversations focused on the ways that people help each another in their communities, leaving no one behind. The goal was to allow people to speak as a group to the rest of society, not as victims but as people with rights who are agents of change.

This article closes a series that has discussed the acts of solidarity and caring for one another that have been so widespread in Latin America’s poorest neighborhoods and communities during the pandemic.

“There are invisible people”

“This crisis,” says Martha Calizaya from El Alto in Bolivia, “makes us rethink how we are leading our lives as human beings.”

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought to the fore the inequalities, neglect, and maltreatment that people in poverty have suffered for centuries. Now, millions have no financial resources to cope with daily costs such as rent, electricity, water, and food. Furthermore, the material aid proposed by some governments does not reach everyone. There are many who don’t even have the documentation they need to prove they exist or access their basic rights. The crisis hits hardest people whom society has left behind or forgotten because no one knows they are there.

- “There are invisible people,” explains Victoria Huallpa, also from El Alto, “people who we don’t realize exist, people who have no documents, who live day to day. There are elderly people who live alone or people who live as caregivers. ‘I have this piece of paper,’ an elderly man told me, showing me a very old birth certificate. ‘I don’t know if with this they’ll give me some help.’ These are people who are practically invisible to the government, and also almost invisible to us, to me, because I didn’t know that there were people in that situation.”

In Guatemala, as in Bolivia, many people are excluded. “Society,” says Luis Zepeda from Guatemala’s capital, “marginalizes families in poverty every day. They have been shunted to the side. They are made invisible by the government, but even more so by society itself. Even though society knows who needs help, who needs food or bread, society still pushes them aside.”

“We are marginalized communities,” insists Aida Morales from Escuintla. “Help has not arrived because these are no-go areas. But this is where aid should have been directed because these are people who do not have access to jobs and live day to day.”

More suffering under lockdown

While discrimination is nothing new to people in poverty, the pandemic has aggravated discrimination across the board – in education, work, health, and access to food and water. As Julia Marcas from La Vizcachera (on the outskirts of Lima, Peru) explains, “For years now we have been living without water or sanitation, and no one listens to us. But it’s worse now – with the quarantine has come more suffering.”

Online Education

Where education is concerned, suffering has also increased. In the context of lockdown, governments have had to find different solutions, offering classes via radio, television, and internet. The challenge is huge for all families, but children in poverty are paying the highest price. Their families have little internet access or have only one – or even no – electronic device at home. Many have barely enough money to make photocopies and are less able to provide help with homework.

“There are children in Marco’s classroom,” recounts Sarita Guevara from Lima, Peru “who have computers and they can go on line. But there are others like us who can not do that. One day I told the teacher that my situation is hard. I live on the hillside and I don’t have those options.

- “But they still ask us to print lessons off the internet. Sometimes there are 8 or 12 sheets to print. Every day I have to get printing and copying done so that my children can do their homework. To avoid spending too much, two sheets have to be copied by hand. Or my son Marcos writes one sheet and I write the other.

“Then I have the rest printed because sometimes writing can be tiring. So, I’ve even become a teacher, four times! Kindergarten, primary, secondary and high school.”

In the midst of great suffering, the poorest parents have had to become real jugglers to be able to help their children. Of course, many teachers are trying to maintain close ties with their students and their students’ families as much as possible. Others, however, have accused the poorest children and their parents of not doing enough.

For example, during the shutdown in Guatemala the government continued to offer school breakfasts to all children through a fortnightly delivery of food to families. Even though this was a basic right, in one of the capital’s poorest communities, one school made this food aid conditional on children handing in their homework. Once again, for the poorest families who depend on aid, a fundamental right has become a tool of humiliation and oppression.

Reaching out to help neighbors

Just as oppression is not new, solidarity within these poor communities is not new either. It did not magically appear during the pandemic. Rather it is part of everyday practices that promote common well-being.

“In these times,” Martha in Bolivia continues, “we have seen that we don’t know our neighbors well enough. We know our next-door neighbors, and those next-door to them. But more than that we don’t know, and we don’t know if they are in need. I have realized that we really need to get to know people, and from there be able to share. People need to get together with others. We are desperate to see one another and we want to be able to do that again. This makes us feel that there’s always a need for other people.”

Such awareness invites everyone to take notice of the people around them, to get to know them, and to move forward together so that no one else is left behind. “I didn’t know there were invisible families, but now I know. I know who they are. They won’t be invisible to me any more. I also hope that this will be the case for the government because we are in for hard times,” concludes Victoria.

We really need one another

“We had a lot to contribute, a lot to say, a lot to give. But no one listened to us when we were children. No one listened to our parents when they became parents. And no one listened to our brothers,” explains Luis. “We need to create places where we can express the things that we are thinking or feeling,” continues Martha. “That helps me to think about things and to get to know myself, to find myself.” “We really need one another,” adds Roxana Quispe.

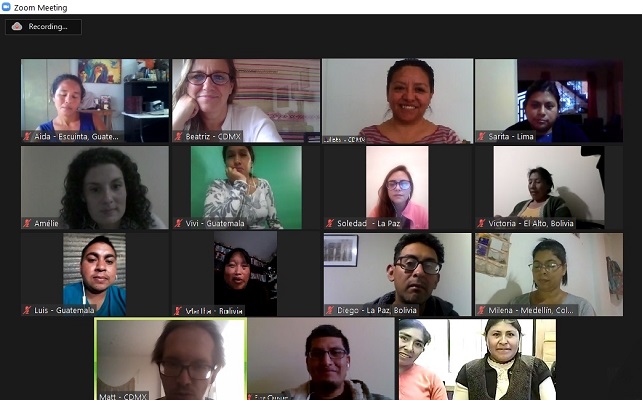

ATD conducted an online seminar on 21 July to broaden horizons and allow others to learn and be inspired. “We want to be recognized as human beings,” explained Luis. “We want others to stop pushing us aside. We want to be given the tools to work, to move forward. We know that they exist but they are not accessible for us. We are people and we can fight. We can move forward from one day to the next.”

Will the world recognize every person on Earth as truly human? Will there be a time when no one is invisible?

Will society recognize these acts of solidarity and support that express so much hope?

Will we fully realize that we really need one another, and that only by coming together can we make a better world?

—

Online seminar: Solidarity, mutual support and resilience: learning from the initiatives of communities living in poverty in Latin America during the pandemic.

Play with YouTube

By clicking on the video you accept that YouTube drop its cookies on your browser.

The members of ATD Fourth World who participated in this online gathering for dialogue, reflection and mutual support are:

From Bolivia: Victoria Huallpa, Paulina Mollericona, Martha Calisaya, Roxana Quispe and Susana Huarachi

From Guatemala: Luis Zepeda, Sindy Sequén, Vivi Luis and Aida Morales, From Brazil: Tatiane Soares,

From Columbia: Milena Foronda

From Peru: Sarita Guevara and Julia Marcas.

These people are all part of an international solidarity group that highlights the efforts of families to develop a range of mutual support initiatives in their communities..

Listening, writing and technological support: Soledad Ortiz and Diego Sánchez from Bolivia; Daniele Mazzarelli from Brazil; Amelie Lemoine and Fray Quispe from Peru; Julieta Pino, Beatriz Monje and Matt Davies from Mexico.

Help conducting the online seminar: Carolina Sánchez Henao from Colombia and Carolina Escobar Sarti from Guatemala.

ATD Fourth World members also contributed to the seminar: Yola Oblitas, Luciano Olazabal, Miriam Pérez and Lara Philibert in Peru; Mariana Guerra in Brazil; Pilar Boche in Guatemala; Rocío Rosales, Marcelo Vargas and Cinthya Torrez in Bolivia; and Gracia Valiente from the ATD Fourth World international communications team.