Time and Tide – and Twitter Trends – Wait for None | Diana Skelton

By Diana Skelton

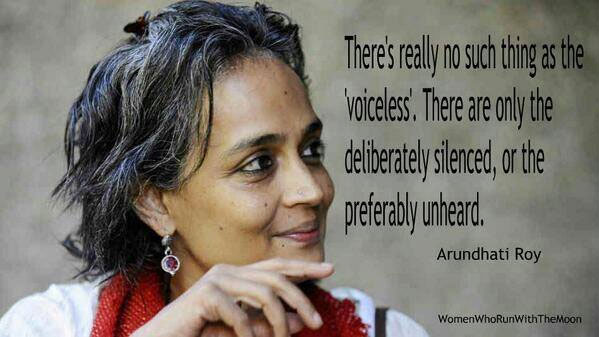

The oppressed have been silenced and unheard for as long as oppression has existed. But the rapid changes in communications in recent years are transforming the nature of what it means to be unheard. Before social media, public discourse about poverty and injustice remained highly controlled: by publishing magnates, professional lobbyists, and a handful of prominent journalists and academics. Today, with almost two and a half billion people enjoying access to the internet, the din of new voices jumping onto the giant global soapbox is growing louder by the minute.

Plenty of good has been coming out of today’s empowerment through crowd-sourcing of information and ideas. Never before have so many people had the chance to be heard by so many others. Everyone, from union organizers to political campaigners to artists, can now engage directly with the public without even pounding the pavement.

But communication remains skewed away from the voices of people in extreme poverty. One reason is lack of access: to literacy, to electricity, to internationally-used languages, or to friends who can help newcomers find their way among the brambles and potholes of Twitter, for example. Only 15% of Africans have internet access, while in North America, the figure is 78%. Even within North America there are differences between university campuses where every single student is equipped with seamless connectivity, and low-income rural communities where people may choose instead to invest their time in real-life links with neighbors they need to depend on.

Another reason people in poverty remain unheard is the quickly increasing speed and volume of the myriad of voices “on their behalf.” In 2004, when ATD Fourth World published How Poverty Separates Parents and Children, there was a loud public debate about Guatemalan adoption fraud: international adoptions of kidnapped children that included women paid to masquerade as mothers abandoning “their children.” Some ATD Fourth World members in Guatemala had lost their children to these kidnapping rings, or locked their children home alone as their only protection. But none of them wanted to speak out about the question. In mourning for their whole community, they were also hurt that public debate was already taking place about them and completely without them. They chose instead to contribute to our study by speaking about other parts of their daily realities, including all the efforts they make to protect their teenage children from the dangers of street violence. On the question of adoption fraud, they chose to remain silent for as long as the powerful voices of international NGOs and public agencies would continue to hammer away at it.

While loud voices are crucial in fighting horrific situations, those voices could become stronger and better-informed by allowing the necessary time for people who have lived through the situation first-hand to take the lead in communicating. When people’s entire lives have consisted of oppression, poverty, and humiliation, they have always known that they — like their parents before them — are expected to be seen and not heard. Of course, none of them are voiceless. They have experience and intelligence that the world needs to learn from. But it takes time and effort to create conditions where they have the room to express themselves without being judged, and the time to choose what they most want to say. And Twitter trends, like time and tide, wait for none.

As well-meaning as social justice posts and blogs can be, too often they also play to stereotypes. Which countries are denounced for human rights abuses? Most often the answer is: the same countries that suffered through decades of colonization, then of economic exploitation by multinational corporations. Dependent on foreign aid, it can be hard for these countries to defend themselves against “donor nations,” like the United States, which have incredible resources and yet allow homelessness, hunger and ill health in their own low-income communities. A woman in Southeast Asia once told me, “Of course I believe in human rights. But the words start to ring hollow when you always hear them used to bash certain countries, while richer countries tend to get off scot-free in the public eye.”

I’ve been thinking of her words during the recent crisis of unaccompanied minors arriving in the U.S. from Central America. Once again, lists are made denouncing all the worst aspects of life in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. It’s true that these countries face enormous challenges. And yet behind the headlines are the unheard voices of people in all three countries who show great courage in resisting violence. Our members in Honduras and Guatemala, for instance, make sacrifices to run Street Libraries for children, opening their horizons to joy and culture despite everything.

But it will take time for them to decide together what they most want to say about today’s headlines — and by then it’s likely that trends will have galloped elsewhere.